Finding Your Quest

Choosing the right problem to solve is personal

In 2021, I spent every other weekend at a sawmill in Northern California. I had spent months studying trees — wood biomass, deforestation, trucking supply chains —convinced I was building “the Flexport for forestry.” I had raised venture capital and done everything by the book.

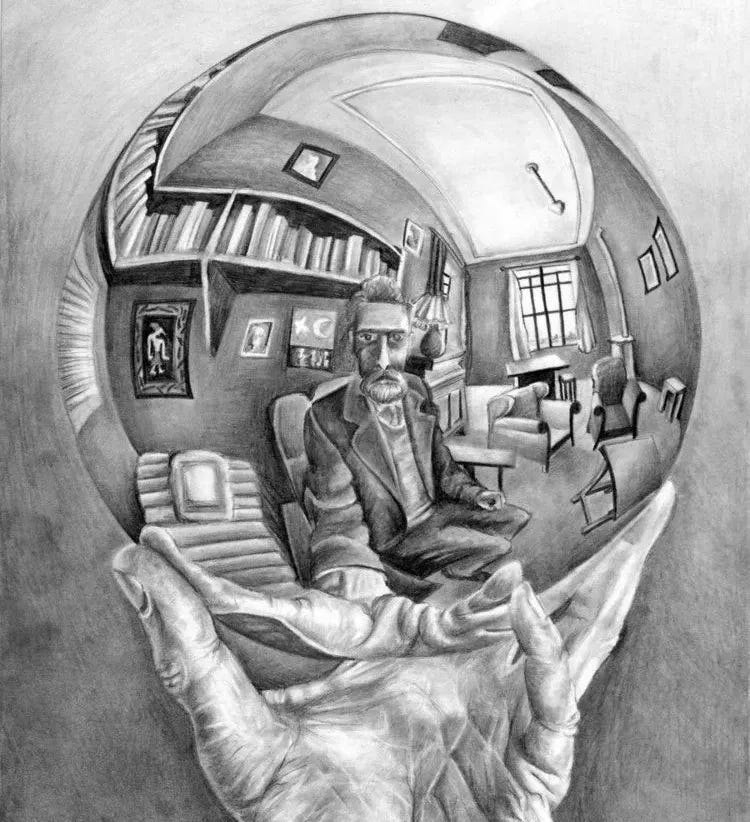

And then, one day, I realized I couldn’t do it anymore. I looked in the mirror and felt like an imposter.

I had done all the “right” things to be perceived as a successful startup founder. I had picked a massive market with a big problem to solve, entered a hot space (climate tech) where VCs were actively investing, and spent months embedded in the industry. But the problem was, I couldn’t wake up every day excited to build. Deep down, I just didn’t care enough.

That moment forced me to rethink everything. If I was going to build another company, I had to care about the problem in a way that was deeply personal. Otherwise, I would constantly be forcing myself to manufacture conviction rather than having it come naturally.

It took two failed startups for me to finally understand: choosing what to build isn’t just about market size or external interest — it’s about choosing a problem that matters enough that I’d wake up every day wanting to solve it.

The First and Second Startup Attempts

Straight out of school, I started an art marketplace (curated ‘Etsy’) and I ran around London trying to onboard emerging artists to the platform. I was woefully naive about market dynamics and the ease of raising funding. After iterating for a year, an attempted move to San Francisco, and a personal heartbreak, the company shut down. At the time, I told myself I had just been inexperienced and that next time I would do things ‘right.’

Five years later, with much more life experience and a newly granted green card, I quit my job as a venture capital investor and set out to build my second startup. This time, I was determined not to make the same mistakes.

I picked a massive market with a clear problem, a hot industry where capital was flowing freely. I spoke to dozens of people in the space and visited lumberyards to deeply understand the supply chain. I wrote an essay outlining my thesis online and raised venture capital funding.

On paper, I had done everything correctly. But inside, I felt tense.

I tried to push through, convincing myself I just needed to develop more conviction. But deep down, I wasn’t motivated enough about carbon removal or building a manufacturing and logistics business. Every day felt like a struggle to care.

I could feel it physically — my energy drained, my body resisting what my mind insisted was the “right” path. I wanted to be a serious founder, one who took markets seriously. But I couldn’t ignore the disconnect. After months of agonizing, I finally accepted the truth: I owed it to my investors and myself to walk away.

I felt like an absolute failure. Two startups down, and I had nothing to show for it.

At that point, I promised myself that if I was going to build another company, it had to be something I deeply cared about.

The Turning Point: Finding Plymouth

John Doerr once coined a framework about missionary vs. mercenary founders. Mercenaries start companies to chase opportunities and optimize for financial returns. Missionaries, on the other hand, are driven by a vision of the world they want to help create.

I had tried so hard to be a mercenary. It didn’t work. I realized I had to put my heart and soul into something if I was going to build it for the long haul. More importantly, I needed that conviction to authentically convince others to join me. If I didn’t believe in the mission myself, how could I ask someone else to?

At this time, I was fortunate to meet Devon Zuegel. She and Maran Nelson were organizing a fellowship for mid-career technologists who wanted to explore alternative ways to impact technology outside the traditional venture-funded startup model.

For the first time in years, I had time, space, and — most importantly — a community to explore what I actually cared about. It was liberating. I hadn’t experienced an environment like this since university.

With this intellectual freedom, I found myself drawn to an idea I had been thinking about for years: immigration. I had gone through an exhausting, confusing immigration process myself. In 2022, I wrote an essay sharing my learnings, and dozens of fellow immigrants reached out to tell me their stories. They had struggled with the same uncertainty — receiving conflicting advice, dealing with endless delays, unsure of whether they even qualified for certain visa pathways.

That essay planted a seed in my mind. What if more people were eligible for visas than they realized? Could technology help uncover alternative pathways for immigrants to build in the U.S.?

Immigration was deeply unsexy to VCs - I was told repeatedly this wasn’t an investable market. I was also told that trying to fix U.S. immigration was crazy. But I didn’t care - I felt energized thinking about how I’d solve my own problem for others. It felt natural. The energy was physically present in my body and I woke every morning excited for the day.

I had found my quest, and even if I had a small shot at making a difference, I wanted to take it.

Around this time, I met Alec and Caleb from the Institute for Progress, who had initially reached out to discuss my work in climate technology. We met for lunch at Le Cafe du Soleil in Lower Haight. But instead of talking about climate, we talked about immigration.

We ideate about helping others navigate O-1 visas. They encouraged me to start building.

After that lunch, I wrote a one-pager outlining my thesis on the problem, my initial solution, and a product strategy. The words flowed so much more easily than anything I had ever written about climate tech. That was a sign.

I started from a ‘problem first’ mindset - instead of thinking about the outcome (e.g., a startup), I thought about how I would solve this problem from first principles. What I discovered was that education was the biggest bottleneck in helping people understand their visa eligibility. I realized that building educational guides and content, would be the first step in solving the problem. There was no technology and no desire to chase external funding. Eventually, over several months, I realized that the quality of immigration providers was bad and that led to building an end-to-end solution.

I didn’t set out to build a company in immigration. It found me.

When I was working on climate tech, everything felt like an uphill battle. But with Plymouth, the work energized me. Instead of forcing conviction, I felt it naturally. That was the difference between chasing a “good” idea and choosing a problem I truly wanted to solve.

Looking back, I’m grateful for the failed startups that led me here. They taught me that the hardest part of entrepreneurship isn’t execution—it was about being honest with myself about why I was building and who I was building for.

Ah, yes. Thanks for the reminder.

This was great. Enjoyed the journey, perspective and aligned with the mission.