Dan Wang: On Writing a First Book, Technology as Hard Power, and China's Engineering State

A behind the scenes talk with New York Times bestseller Dan Wang, author of "the best recent book on China"

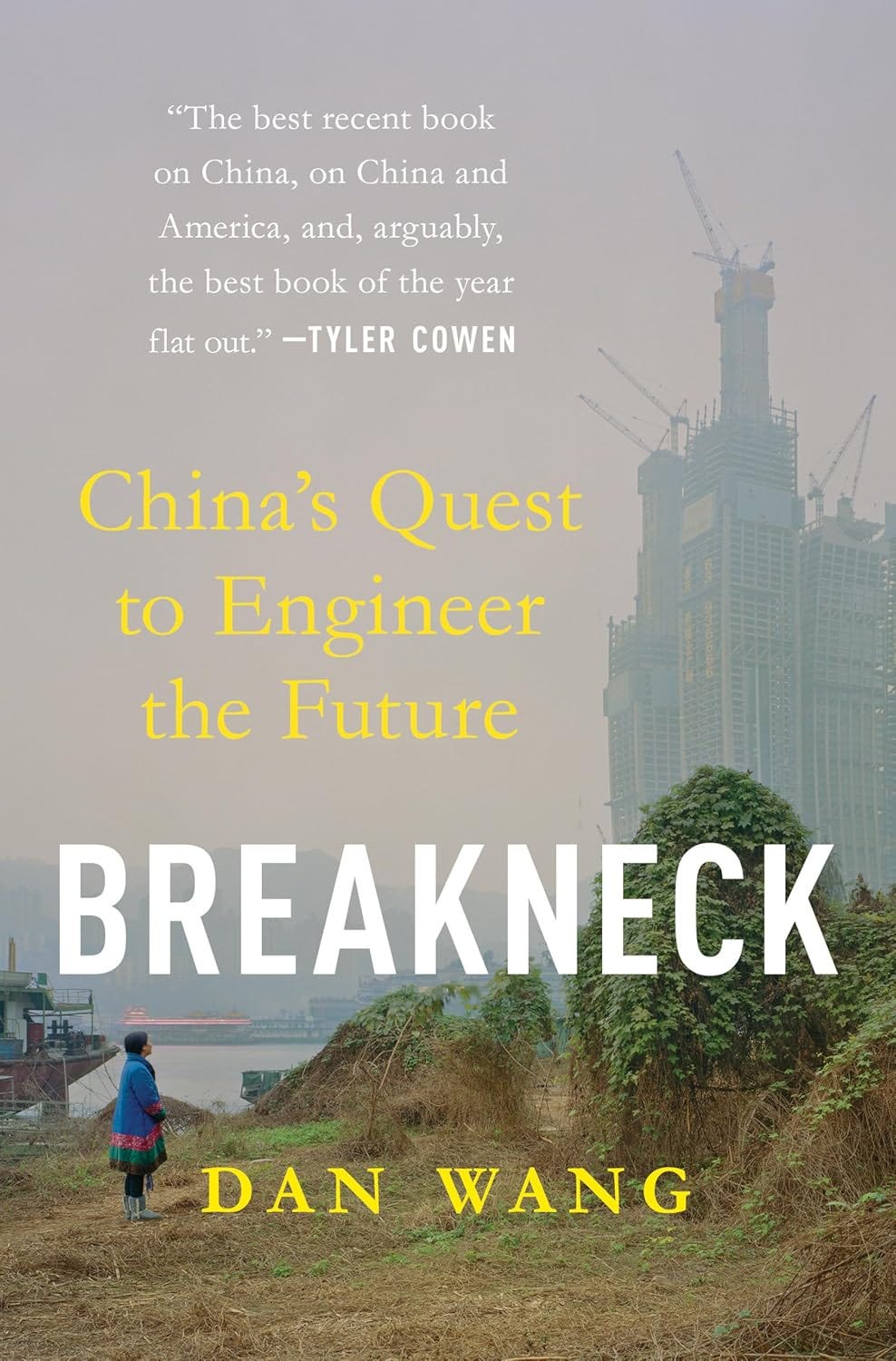

When I spoke with Dan Wang at the Interact Symposium about his new book Breakneck: China's Quest to Engineer the Future, the conversation centered around two competing ways of building societies - the U.S. and China. Dan explores these societies in his latest book, which showcases Wang’s distinct writing style - part memoir, part historical analysis, part political commentary.

Wang explores the two realities he’s lived in. The U.S., where he studied and worked in Silicon Valley, and China, where he spent six years, several during its zero-COVID lockdowns. The framework he developed -- the “lawyerly society” versus the “engineering state” -- is simple but reveals a lot about why the world looks the way it does.

Writing as Craft

Dan is best known for his annual letters -- long, thoughtful analyses of China that earned him a cult following. Dan wanted to write a book because, in his words, they are “totemic objects”- something you can hand to a policymaker, a CEO, or a student years later. That discipline of writing long, carefully argued essays each year was what allowed him to eventually take on the bigger canvas of a book.

There’s a lesson here for anyone building: practice in small increments compounds into work that lasts. And sometimes, you need the weight of a physical artifact to push an idea into the world.

The Lawyerly Society vs. the Engineering State

The centerpiece of Breakneck is the contrast between how the U.S. and China are governed: - lawyers run America, and engineers run China. America’s presidents, senators, and governors overwhelmingly come from law schools. They are trained to argue, to block, to litigate. The upside is resilience -- the U.S. rarely imposes disastrous policies like the one-child rule. The downside is stagnation: trains delayed, housing undersupplied, power grids outdated. America’s institutions excel at saying no.

China is an engineering state. Its leaders are trained to build: highways, dams, power plants, entire cities. They move fast, sometimes recklessly. Zero COVID and one-child were policies executed with ruthless precision. Infrastructure appears overnight, but so do restrictions on speech and freedom.

Neither model is enviable. But the juxtaposition makes sense of the lived reality: why America tolerates dysfunction, why China suppresses dissent, and why both countries often feel broken in opposite directions.

Me (left) and Dan (right) chatting about Breakneck at the 2025 Interact Symposium, hosted at Stable Cafe in San Francisco, CA.

Technology as Hard Power

One of Dan’s most powerful points is that technology is not just code or hardware. It’s power, aesthetics, and geopolitics. China’s elites focus on the belief that China’s historical defeats to both the West and fascist Japan were because these powers were scientifically and technologically more advanced. That urgency explains its relentless drive to catch up and surpass. The US, by contrast, doesn’t have one vision. Our strength is pluralism -- startups bloom across crypto, AI, SaaS, and defense -- but the weakness is fragmentation. There is no singular narrative that unites them.

And then there’s Europe. Dan put it bluntly: Europe doesn’t share America’s dynamism in services, nor China’s industrial speed and quality. Walking around Paris or Berlin, he argues that you don’t feel the same restless push toward the future.

Takeaways for both societies:

At the end of our conversation, I asked Dan to share his recommendations from the book. He argues that America could use 20% more of China’s engineering spirit -- enough to actually build housing, energy infrastructure, and transit. China could use 50% more of America’s lawyerly restraint -- enough to respect individual rights and unleash creativity.

For individuals, these aren’t abstract contrasts. They are the environment you operate in. The society around you shapes every decision about where to live, hire, or expand. Can you move quickly? Will the infrastructure support you? Will your rights be respected if you succeed?

Dan’s book is a reminder that technology is never neutral. It encodes values.

That, to me, is the real takeaway from talking with Dan Wang: his framework isn’t just about the US and China. It’s about all of us deciding what kind of society we are building, and whether it will be a place worth belonging to.